Norman Shaw

Eternal Surging – Consciousness and Gaelic Sonorous Landscape

(First published in Intermedial Art Practices as Cultural Resilience (Routledge: Routledge Advances in Art and Visual Studies, 2025), edited by Lindsay Blair and Camille Manfredi, p.178-187)

The audio-visual installation Highland River (Shaw 2008) (Figs.1 and 2) shows the patterned surface of a peaty Highland river in constant motion (click here for video). The soundtrack is composed from recordings of Gaelic psalm singing retrieved from cassette recordings of Free Church services from the Isle of Lewis in the 1970s and ‘80s, layered and remixed as an ambient soundscape. (Shaw 2007)

Fig. 1 – Norman Shaw, Highland River (installation view), 2008, digital video projection with audio, 10mins. Shown at: Printing The Gaidhealtacht, Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art & Design, University of Dundee, 2023; Alchemy Film and Moving Image Festival, Hawick, 2011; The Rediscovery of Highland Art, City Art Centre, Edinburgh, 2010/2011; Eskimo, Eskmills Gallery, Musselburgh, Edinburgh, 2008.

Fig. 2 – Norman Shaw, Highland River (still), 2008, digital video projection with audio, 10mins.

The Gaelic psalms are sung without musical accompaniment, where the ‘precentor’[1] sings each line solo and the congregation slowly repeat what he has sung. This practice originates from a time when congregations were illiterate. It is an aspect of the oral culture of the Gael, a world made of sound that stretches back to Ossian the ancient Celtic bard whose blindness highlights the aural nature of his world. Ossian is sonically continuous with the environment. His songs reverberate in the rocks, trees, rivers, lochs and skies of the Highland landscape. The folds of the rocks and the whorls in the river are the waveforms of his music, echoes of his eternal surging songs. In the film, the fluid forms of the river arise and retreat in the current, objects that are never static nor separate from the general flow of what we call a ‘river’, but in a constant state of becoming, in parallel with the surging psalm-singing

Auditory space can dissolve distinctions between subject and object whilst evoking absence through sound, according to Edmund Carpenter and Marshall McLuhan:

'Auditory space […] can be filled with sound that has no ‘object’, such as the eye demands […] Poets have long used the word as incantation, evoking the visual image by magical acoustic stress. Preliterate man was conscious of this power of the auditory to make present the absent thing. Writing annulled this magic because it was a rival magical means of making present the absent sound.' (Carpenter & McLuhan, 43)

James Macpherson’s eighteenth-century renderings of Ossian’s poems into English may indeed have annulled the auditory magic of Ossian’s work, but their cultural significance is well documented. Significantly, they strongly influenced William Blake’s poetic style and imagery, evoking the voice of the bard which conflates temporalities:

Hear the voice of the Bard!

Who Present, Past, & Future sees (Blake, 2)

Highland River is an extension of doctoral research undertaken at the University of Dundee, exploring the role of Ossianic sonority in creating the mythic Highland landscape (Shaw, 2003). A series of line drawings, Sonorous Maps (Figs.3 and 4), constitute a key aspect of this research.

Fig. 3 – Norman Shaw, Sonorous Map, Sunart, 2002, ink on paper, 29x19cm.

Fig. 4 – Norman Shaw, Sonorous Map, Knoydart, 2010, ink and graphite pencil on paper, 55x43cm.

Art historian Murdo Macdonald wrote:

'Shaw's line drawings conjure up not the image of the bard but a cultural landscape of complex, tightly packed contours that echo what he calls the ‘sonorous’ nature of Macpherson's text, the very feature that William Blake was to find so attractive and was to imitate in his own writings.' (Macdonald, 113-114)

These drawings are visualisations of the sonorous nature of what we call landscape, where soundwaves become landwaves, as in Ossian’s eternal music; diagrams of the land’s “forces, densities and intensities.” (Deleuze and Guattari, 343) They present what we call landscape in terms of sonic phenomena, conflating dualities of subject and object. Apparent objects are wholly interdependent upon each other, entangled and interpenetrating. In a phenomenological sense, they present landscape before thought distinguishes between subject and object.

'The object and the viewer, which are both conceived as existing in their own right, independent of the thought that thinks them, are both concepts.' (Spira, 146)

The drawings have been exhibited adjacent to comparable drawings by eighteenth-century Scottish artist Alexander Runciman[2]. A drawing by Alexander Runciman embodies this fundamental unity, showing Ossian “at one with nature.” (Macmillan, 122) The work of quantum physicist David Bohm provides scientific validity for this vision of inherent unity of subject and object:

'Ultimately the entire universe, with all its ‘particles’, (including these constituting human beings, their laboratories, observing instruments, etc.) has to be understood as a single undivided whole, in which analysis into separately and independently existent parts has no fundamental status.' (Bohm, 221)

For Bohm the quantum theory shows that

'one can no longer maintain the division between the observer and the observed […] Rather, both observer and observed are merging and interpenetrating aspects of one whole reality, which is indivisible and unanalysable.' (Bohm, 9)

The originator of modern quantum theories Max Planck emphasises that this primary reality is consciousness itself:

'I regard consciousness as fundamental. I regard matter as derivative from consciousness. We cannot get behind consciousness. Everything that we talk about, everything that we regard as existing, postulates consciousness.' (Planck)

This ‘consciousness-first’ understanding of reality, where “reality is a vast unity of consciousness” (Yetter-Cappell: 79) lies at the heart of idealism in philosophy:

'one comes to think that there is little reason to believe in anything beyond consciousness and that the physical world is wholly constituted by consciousness, thereby endorsing idealism.’ (Chalmers, 353)

This understanding underpins all mystical traditions, and can be traced back to the Vedas in the East and Neoplatonism in the West.

Bohm employs the image of a river with whirlpools to explain how apparently separate objects relate to this undivided whole, where a whirlpool is perceived as an object yet is continuous with the totality. Scientist Bernardo Kastrup similarly utilises the image of a river with whirlpools, or vortices, as a metaphor for how objects arise within the medium of mind (Kastrup 2014, 80). In The Fold, Gilles Deleuze invokes the image of interpenetrating vortices to describe the inseparability of parts of ‘matter’:

'Dividing endlessly, the parts of matter form little vortices in a maelstrom, and in these are found even more vortices, even smaller, and even more spinning in the concave intervals of the whirls that touch one another.' (Deleuze, 5)

These vortices are in a constant state of becoming, and the model of the flowing river with whirlpools implies that we can travel upstream to its source. Highland River is intended to point back to that source. Its title pays respectful tribute to the book of the same name by Highland writer Neil Gunn, which describes the hero Kenn’s metaphysical journey “into the source” (Gunn, 59), paralleling the upstream journey of the mythic Salmon of Wisdom. Deleuze and Guattari specifically refer to the migration of salmon as “pilgrimages to the source.” (Deleuze and Guattari, 325)

Strikingly illustrative of Deleuze’s image of interpenetrating vortices are the arrangements of spirals within spirals in Pictish and Celtic art of the late medieval period, such as The Shandwick Stone in Easter Ross which features at its base a large mandala-like arrangement of interlocking spirals. (Fig.5)

Fig. 5 – Joseph Anderson, Panel of Spiral Ornament, Shandwick, 1881. https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Shandwick_Anderson_1881b_Fig_79_scotlandinearlyc00anderich_0154.jpg

Similarly, art of the illuminated manuscripts of the early Celtic church feature a fractal proliferation of whirring spiral patterns, as in the Chi Rho page of The Book of Kells. (Fig.6)

Fig. 6 – Chi Rho page, Book of Kells, 9th Century.

https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:KellsFol034rChiRhoMonogram.jpg

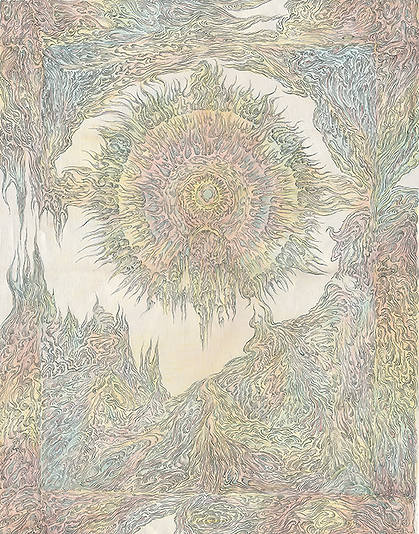

This kind of Celtic fractality characterises a series of large coloured drawings that developed from methods used in the Sonorous Maps. Commenting on the drawing Tir Nan Analog (Fig.7), Gaelic scholar and poet Meg Bateman writes that this evocation of fractals gives “a modern explanation for a mystical unity of nature.” (Bateman and Purser, 57)

Fig. 7 – Norman Shaw, Tir nan Analog, 2019, ink and coloured pencil on paper, 59.5x77.5cm

Referencing Runciman’s images of Ossian, Bateman highlights the Gaelic bards’ practices of sensory deprivation to attain the same ‘mystical unity’ that informs the author’s research. The bards’ techniques of brain-function impairment engender what Kastrup calls “self-transcending” experiences, “often described as ‘mystical’ and ‘awareness expanding’” (Kastrup 2017, 33), enriching the inner life and pointing to a kind of consciousness that transcends dualities. Bateman asserts that these practices played an important part in bardic culture into the sixteenth, seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, and she suggests that Ossian’s blindness represents a deliberate practice, where hearing, taste, touch and, above all, sight were excluded to induce mystical visions:

'As much as we can tell, these practices conflated dualities, rational and chronological thinking in the pursual of mystical, creative and mantic visions. The contemporary Scottish artist, Norman Shaw, engages with these ideas.' (Bateman and Purser, 57)

Subsequent drawings in this series, Ascended Farlight Array (Fig.8) and Metasensory Geoluminal Formation (Fig.9) respond structurally to the mandala-like pages in manuscripts such as The Book of Kells (Fig.6). The Book of Kells, also known as The Book of Columba, was produced by monks of the order of Saint Columba, probably on the Island of Iona, where the Irish St Columba founded a monastery.

Fig. 8 – Norman Shaw, Ascended Farlight Array, 2019, ink and coloured pencil on paper, 77.5x59.5cm

Fig. 9 – Norman Shaw, Metasensory Geoluminal Formation, 2019, ink and coloured pencil on paper, 53x38cm

The author collaborated with Meg Bateman on a project commissioned by the Earagail Arts Festival in Donegal, Ireland, celebrating the 1500th anniversary of St. Columba’s birth in 2021. Two drawings were produced in response to two poems by Bateman. (Bateman and Shaw, 12-23)

Colmcille’s Vision (Fig.8) responds to Bateman’s adaptation of a 12th Century Gaelic poem: “Delightful it would be on the breast of an island.” As an ecstatic hymn to solitary contemplation of nature as a path to divine inspiration, the poem embodies the mystical aspects of the legacy of Saint Columba, where the divine is immanent in nature. There is a cyclical, or non-linear element to Gaelic ontology. Everything is caught up in the ‘eternal surging’, to borrow a phrase from Bateman’s poem.

Fig. 10 – Norman Shaw, Colmcille’s Vision, 2021, ink and coloured pencil on paper, 77.5x59.5cm

Odhran’s Vision (Fig.9) responds to Bateman’s poem ‘Doubt’. The poem explores the ambiguous relationship between early Celtic Christianity and indigenous spirituality. Bateman suggests that these two worlds are perhaps not as far apart as one might initially suppose. The first part of the poem tells the Story of Odhran, who was buried alive as a foundation sacrifice under what is now St. Odhran’s Chapel on Iona, expecting to go to heaven as a reward. He resurrected alive three days later, claiming to have gone to Hell instead, and that it’s not as bad as they say. To silence Odhran’s heresy, Columba clubbed him over the head and re-buried him. The poem goes on to describe a dialogue between Columba and the sea-god Mongan. “Taken together,” writes Bateman, “the tales suggest a scepticism about Christianity’s monopoly of cosmology and acknowledge greater complexities.” The drawing is an image of chthonic separation, an ambiguous dialectic of above and below, within and without, invoking in Bateman’s words, “the spot where knowledge and ignorance had died, were born and buried.” (Bateman and Shaw, 17).

Fig.11 – Norman Shaw, Odhran’s Vision, 2021, ink and coloured pencil on paper, 77.5x59.5cm

References

Bateman, Meg and Purser, John. Window to the West – Culture and Environment in the Scottish Gàidhealtachd. Clò Ostaig, 2020.

Bateman, Meg and Shaw, Norman. “Teagmhachd” and “Bu taitneach a bhith an uchd eilein.” Cosàn Cholm Cille. Earagail, 2021.

Blake, William. “Introduction.” Songs of Experience (1794). Dover, 1984: 2.

Bohm, David. Wholeness and the Implicate Order. Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1980.

Carpenter, Edmund and McLuhan, Marshall. “Acoustic Space.” McLuhan, Marshall. Media Research: Technology, Art and Communication. Routledge, 2014: 39-44.

Chalmers, David J. Idealism and the Mind-Body Problem. Seager, W. ed. The Routledge Handbook of Panpsychism. Oxford University Press, 2021: 353-373.

Deleuze, Gilles and Guattari, Felix. A Thousand Plateaus – Capitalism and Schizophrenia. Athlone, 1988.

Deleuze, Gilles. The Fold – Leibniz and the Baroque. Athlone, 1993.

Gunn, Neil M. Highland River. Porpoise Press, 1937.

Kastrup, Bernardo. Why Materialism is Baloney. Iff Books, 2014.

Kastrup, Bernardo. “Self-transcendence correlates with brain function impairment.” The Journal of Cognition and Neuroethics. Center of Cognition and Neuroethics, University of Michigan-Flint and the Insight Institute of Neurosurgery and Neuroscience. Vol.4, No.3: 33-42. Jan 2017. A summary of this article also appeared in Scientific American on 29th March 2017 – available at https://blogs.scientificamerican.com/guest-blog/transcending-the-brain

Macdonald, Murdo. Rethinking Highland Art. Royal Scottish Academy, 2013.

Macmillan, Duncan. Scottish Art 1460 – 1990. Mainstream, 1990.

Planck, Max. Interviewed by J.M.W. Sullivan. “Interviews With Great Scientists, VI: Max Planck.” The Observer, 25th January 1931, p.17 column 3.

Shaw, Norman. “Ossianic Sonority and the Sonics of The Unpresentable.” PhD diss., University of Dundee, 2003.

Shaw, Norman. “Salm on Saturn.” Scotland’s Music – A Radio History (John Purser). Episode 48 – New Religions? BBC Radio Scotland, Sunday 9th December 2007.

Shaw, Norman. “Highland River.” 2008. Digital video projection with audio, 10mins.

Shown at: Printing the Gaidhealtacht, Duncan of Jordanstone College of Art & Design, University of Dundee, 2023; Alchemy Film and Moving Image Festival, Hawick, 2011; The Rediscovery of Highland Art, City Art Centre, Edinburgh, 2010/2011; Eskimo, Eskmills Gallery, Musselburgh, Edinburgh, 2008. https://www.normanshaw.land/video

Spira, Rupert. The Transparency of Things. Sahaja/New Harbinger, 2016.

Yetter-Cappell, Helen. “Idealism Without God.” Goldschmidt, Tyron and Pearce, Kenny eds. Idealism: New Essays in Metaphysics. Oxford University Press, 2017: 66-81.

[1] The precentor on these recordings is the author’s father, the Rev. Neil Shaw.

[2] The Rediscovery of Highland Art exhibition, City Art Centre, Edinburgh, 2010/2011. Sonorous Map: Sunart is also reproduced alongside Alexander Runciman’s etching Cath-Loda in Macdonald, Murdo. Rethinking Highland Art. Royal Scottish Academy, 2013: 46-47